The New York Times’ Falun Gong Distortion

How the "paper of record" repeatedly failed to cover atrocities against Falun Gong, and amplified Chinese Communist Party propaganda with devastating results

New York Times headquarters (stock.adobe.com)

Key Findings

The Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) violent campaign to eradicate the Falun Gong spiritual group is one of the most serious human rights crises taking place in China, affecting tens of millions of people and costing billions of dollars. Yet it has been severely underreported and its victims largely discarded and maligned. As the 25th anniversary of this tragedy approaches, the Falun Dafa Information Center examined coverage of Falun Gong in The New York Times, an agenda-setting paper, and found disturbing results.

- Widespread misrepresentation: The New York Times’ coverage has significantly and irresponsibly distorted the story of Falun Gong, be it in terms of the nature of the practice or the scope of the persecution. This report details these findings—one of the most significant failures in international reporting over the last 25 years, with wide-ranging implications for people in China and around the world.

- Frequent inaccuracies: The New York Times’ coverage of Falun Gong is riddled with factual errors. These range from relatively benign assertions to more damaging labels that fuel hatred toward the group. The New York Times’ characterization of Falun Gong teachings and beliefs has been predominantly inaccurate and negative, often following the CCP’s framing. The image of Falun Gong that emerges from the coverage is at odds with the lived reality of practitioners and evaluations of experts on Chinese religion.

- Uncritically following CCP framing on the persecution: The Times’ coverage has favored Chinese government sources when reporting on the violent campaign launched by the regime in July 1999 since its inception. The paper has uncritically repeated and seemingly internalized key aspects of the regime’s framing of the campaign. This has occurred and persisted even when the claims contradicted the Times’ own early reporting and emerging research by human rights groups.

- Silence on Falun Gong persecution: For the past 20 years, the New York Times has been exceptionally silent on atrocities against Falun Gong practitioners, including the forced organ harvesting of prisoners of conscience. Incredibly, the Times’ has published no news story focused on rights abuses facing Falun Gong practitioners in China since 2016, even as these violations continue on a large scale. The paper ignored major reports by human rights groups and the 2019 London China Tribunal on forced organ harvesting, as well as ongoing high-profile individual cases of prison sentences and deaths in custody. At least one former Times journalist reported being barred by editors from investigating organ transplant abuses against Falun Gong practitioners and other prisoners of conscience.

- Contrast to competitors: The Times’ coverage of the Falun Gong human rights crisis during its nascent stage, was significantly different from other major papers. While the New York Times was seemingly preoccupied with distorting Falun Gong beliefs and improving ties with the Chinese communist leadership, its peers like the Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, and others produced ground-breaking investigations and award-winning journalism about the human toll the crackdown was taking, the architecture of the campaign, and inaccuracies in the regime’s propaganda against Falun Gong. Jumping ahead to 2019, outlets like the Guardian and Reuters reported on the findings of the China Tribunal, which the Times ignored.

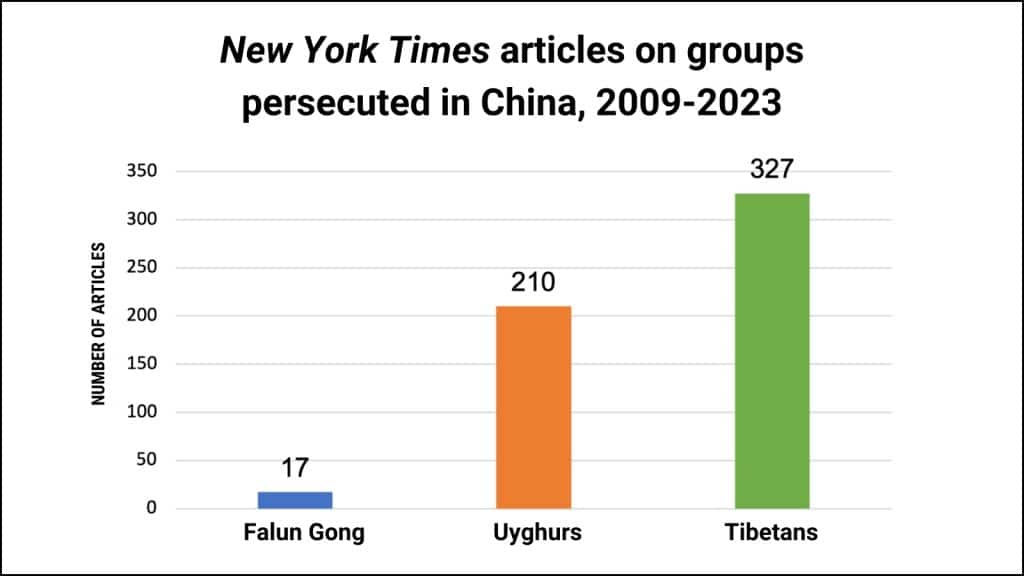

- Contrast to coverage of Uyghurs and Tibetans: The Times’ silence on Falun Gong is even more stark when compared with the paper’s coverage of human rights crises facing other religious and ethnic groups in China, namely Uyghurs and Tibetans, whose population size is much smaller than the Falun Gong community in China. Since 2009, the paper has published hundreds of articles, including investigative reports and sympathetic profiles of individual Uyghur and Tibetan prisoners, as well as dozens of op-eds by scholars and members of these communities. By contrast, it published only 7 stories about the persecution of Falun Gong and not a single op-ed by a Falun Gong practitioner.

- Increasing distortion over time: In recent years, the Times’ coverage has become even more problematic. Alongside complete silence on rights abuses facing Falun Gong practitioners, the few articles it has published on Falun Gong have been openly hostile, targeting organizations founded by practitioners. These negative articles repeat prior inaccuracies, incorporate new ones, and in practice, serve the CCP’s goals of maligning Falun Gong and stymying the party’s critics.

- Lost lives and information gaps: The impact of the Times’ distorted reporting and irresponsible treatment of Falun Gong practitioners as “unworthy victims” has contributed to the impunity enjoyed by perpetrators and robbed their victims of vital international support, undoubtedly resulting in greater suffering and loss of life throughout Mainland China. Given the strong intersection between the regime’s campaign against Falun Gong and topics central to daily life in China—internet censorship, public surveillance, forced labor, and rule of law deficiencies—the Times’ silence on Falun Gong has deprived policymakers and businesses of critical information for navigating today’s China.

- Beneficiaries of the Times’ distortions: By contrast, the Chinese regime has benefited immensely from the Times’ coverage, gaining traction for its agenda to marginalize Falun Gong and obscure the crackdown against it, while also providing credibility to anti-Falun Gong propaganda domestically and globally. Meanwhile, the Times has avoided far more severe penalties from the Chinese regime (and perhaps even gained favors) by taking a hands-off approach to reporting on the CCP’s systematic campaign of religious persecution against Falun Gong.

1. Why This Report?

A 30-year-old man dies in a Chinese prison, jailed for handing out leaflets, while news of his death posted by a former classmate goes viral on Twitter. A technology firm adds a special “alarm” to surveillance devices sold to Chinese police to alert them to the presence of a member of a persecuted religious group. Police in China conduct simultaneous raids in a single city, detaining dozens of grassroots activists who defiantly and nonviolently challenged CCP) censorship and religious persecution. Survivors of labor camps consistently report having been forced to package products for export, including toys, chopsticks, and holiday decorations.[1]

To an average news consumer, such incidents would at face value seem like newsworthy stories, ones of human interest as well as policy and business relevance. Indeed, in many circumstances involving some communities in China—rights lawyers, Uyghurs, Tibetans—the New York Times has devoted significant resources, attention, and column space to such accounts.

But if the same story involves a Chinese person who practices Falun Gong, a meditation and self-improvement discipline practiced by tens of millions worldwide, the paper’s perspective is strikingly different. Not only are the victims’ plights typically treated with silence and indifference, but even more damaging—when they are reported—articles are riddled with misrepresentations, inaccuracies, and outright hostility, displaying a shocking degree of unprofessionalism and bias.

It may seem like an outrageous assertion to state that the so-called “paper of record” has behaved in such an irresponsible and unethical manner. And yet, as an organization whose mission is to document human rights violations against Falun Gong practitioners in China and to give victims a voice to tell their story, the Falun Dafa Information Center (henceforth “InfoCenter”) has been dismayed time and again over the past two decades at the Times’ depictions of Falun Gong and the persecution its believers face, given how stark a departure these have been from the real, lived experience of the community.

As the 25th anniversary of the CCP’s persecution of Falun Gong approaches in July 2024 and as the Times’ reporting on Falun Gong has in recent years taken a more hostile and disturbing turn, the InfoCenter felt the time was ripe to systematically examine and analyze the paper’s coverage.

The report before you is the outcome of that process, a detailed set of findings on how a leading newspaper overlooked and distorted one of the most significant human rights crises of our time. It thereby deprived victims of life-saving international attention and robbed readers of critical information that might impact policy decisions or business investments in a rising global power.

Many of the patterns described below are not necessarily isolated to the Times, but the paper’s problematic reporting—and all too often, silence—have been more pronounced than its competitors. They have also been more impactful, given the Times’ unique agenda-setting role in the U.S. and global media landscape, a position which engenders greater responsibility to get stories right and to maintain a high journalistic standard.

We at the InfoCenter did not take the decision to publish this report lightly. Like many Americans, we grew up viewing the Times as a trusted news source, yet every time it published a piece about our community, we found ourselves egregiously and repeatedly disappointed. An earlier version of this research was produced in 2008 and shared privately with the Times’ ombudsman, but remained unpublished.

Over 15 years later, we have updated and revised those findings and decided to publish them in the hopes of setting the record straight and at a time when others—including former Times staff—have increasingly voiced concerns about political and ethical problems at the paper, and as a new trend has emerged of actively hostile reporting on Falun Gong.

As you read the coming pages, we simply ask that you keep an open mind. And perhaps, consider—if your sister, or mother, or son were rotting in a Chinese prison, facing who-knows-what horrors for simply practicing a meditation and spiritual discipline that improved their well-being or handing out leaflets exposing other innocent people’s torture—how would you feel about the way the Times was depicting them and their plight?

Research Methodology

In compiling the data for this report, the InfoCenter relied primarily on a database of New York Times articles extracted directly from the paper’s website via the Times Article Search API covering the period of 1999 to 2024. Each article extracted included fields such as headlines, lead, abstract, date, section, page, byline, article URL, and the full text.

The extracted articles were stored in an SQLite database. Researchers then extracted relevant subsets of data based on terms present in different fields, manually reviewed them to remove duplicates, and performed analysis and coding. A primary subset of 159 articles were identified as focusing on Falun Gong, based on reference to the term in the headline, lead, or abstract. For each data point, the InfoCenter has included an explanation of the specific methodology used to identify it from the larger dataset.

Essential Background

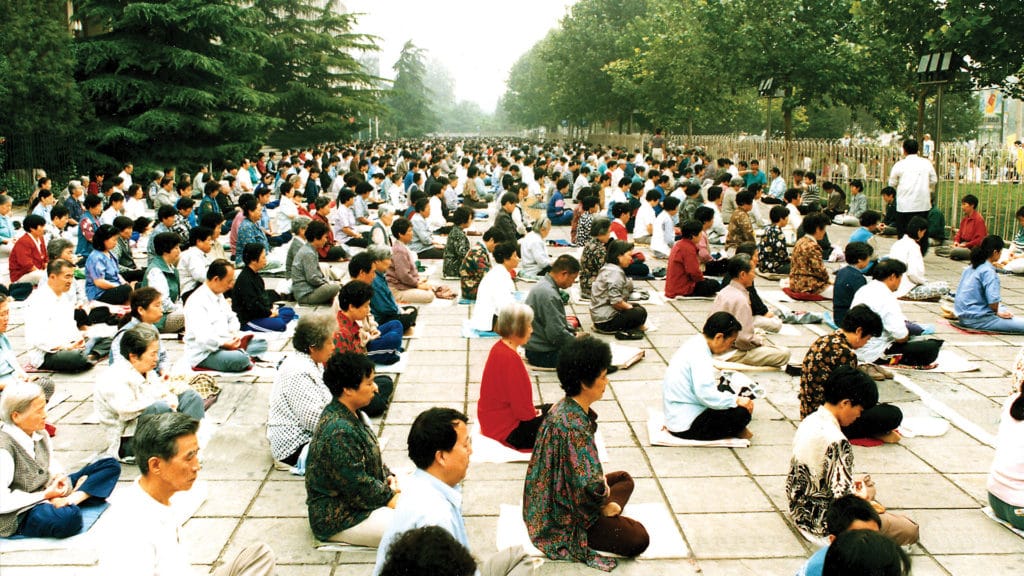

A Falun Gong practice site in Beijing, 1998

Falun Gong, also known as Falun Dafa, is a spiritual practice in the Buddhist tradition. Falun Gong combines meditation and gentle qigong exercises with a moral philosophy centered on the tenets of Truthfulness, Compassion, and Tolerance (or in Chinese, Zhen 真, Shan 善, Ren 忍). People who practice Falun Gong aspire to live by these principles in their daily lives. The practice has no clergy, place of worship, or formal organizational structure. Many who practice Falun Gong express that it is a deeply personal endeavor. They may read Falun Gong books and do the exercises on their own, or gather in small groups to do these together.

In 1992, Mr. Li Hongzhi introduced the practice to the public in China, where it spread rapidly. In the 1990s, the practice was repeatedly praised by Chinese government officials and state-media. By 1999, the Chinese government itself estimated that there were 70 million people practicing Falun Gong in China, more than the membership of the CCP at the time. Paranoid of this popularity and Falun Gong’s independence from CCP control, then-communist leader Jiang Zemin ordered that the practice be “eradicated” in the summer of 1999. Jiang established an extra-legal security force—known as the 6-10 Office—and gave it free rein to use all means necessary to crush Falun Gong.

On July 20, 1999, the regime launched a full-fledged campaign to wipe out the practice, complete with public book burnings, mass detentions of known practitioners and local coordinators, and state-media fabrications demonizing the practice and its founder. Over the past 24 years, millions of Falun Gong practitioners in China have been subjected to police abduction, imprisonment, torture, and death while in custody. Over 5,000 cases of Falun Gong practitioners dying due to persecution have been documented. Furthermore, untold numbers (likely hundreds of thousands according to the China Tribunal’s estimate) have been killed and their organs extracted to fuel a booming, multibillion dollar organ transplant industry in China.[2] By many accounts, the Chinese state’s campaign against Falun Gong amounts to crimes against humanity; several experts and prominent human rights attorneys have designated it genocide.[3]

Despite these horrors, millions—even tens of millions—of people continue to practice Falun Gong in China, encouraged by the improvements it has brought to their physical and mental well-being. They are joined by hundreds of thousands of others in over 100 countries around the world, transcending barriers of culture, language, and ethnicity.

For more on Falun Gong and the persecution faced by practitioners, see “What Is Falun Gong?” and “Violent Suppression of 100 Million People.”

2. Ominous Beginnings

During the nascent stage of the Falun Gong human rights crisis, the New York Times was seemingly preoccupied with distorting Falun Gong beliefs and currying favor with the Chinese communist leadership, even as the Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, and others produced ground-breaking and award-winning journalism about the crackdown.

Western media were taken by surprise by a peaceful gathering of over ten thousand Falun Gong practitioners outside the Zhongnanhai leadership compound in April 1999. The practitioners were responding to escalating harassment and the recent arrest of 40 people in a nearby city.[4] Very little was known in the West about the spiritual practice, despite its growing popularity among Chinese people over the prior seven years.

As events escalated, culminating in the launch of a nationwide persecution campaign in July 1999, Western media coverage remained relatively shallow, offering a combination of Chinese government statements and basic facts of visible events. As expected, throughout the latter half of 1999, Western media investigation into and reporting on Falun Gong gained more depth as reporters on the ground gained better insight into the nascent crisis.

Over the next three years, however, a stark and disturbing divergence occurred between the New York Times’ coverage of Falun Gong and other major media.

Investigative reporting and debunking of CCP propaganda by other major media

Beginning in late 1999, the Wall Street Journal embarked on a bold and thorough investigation into the Falun Gong human rights crisis, resulting in a Pulitzer Prize-winning series of 10 articles published throughout 2000, disclosing the rampant detention and torture of Falun Gong practitioners, including deaths in custody.[5] Additionally, in 2002, the Wall Street Journal was the first major Western news outlet to scrutinize the CCP’s transnational repression campaign against Falun Gong in the United States.[6]

During this same time period the Washington Post offered ground-breaking coverage of Falun Gong in China. The November 12, 1999 article “Cracks in China’s Crackdown” was one of the first international media reports to accurately identify then-CCP leader Jiang Zemin as the sole instigator of the crackdown and the one who gave the order to label Falun Gong a so-called “cult.”[7] The February 6, 2001 article “Human Fire Ignites Chinese Mystery” was the first and only major Western news story to investigate the individuals allegedly involved in a Tiananmen Square self-immolation incident, whom the CCP claimed were Falun Gong practitioners.[8] The article demonstrated that at least some of the participants did not practice Falun Gong, despite the CCP’s propaganda onslaught using the event to vilify the practice and turn the Chinese and international public against Falun Gong. And with the August 5, 2001 article “Torture Is Breaking Falun Gong,” the Washington Post became the first Western media outlet to publish details of Beijing’s explicit directive to use torture on Falun Gong, and the devastating cost on people around the country.[9]

Shallow reporting and negative portrayals of Falun Gong by the New York Times

During this same time period, by comparison, Times coverage of Falun Gong, with two possible exceptions, lacked on-the-ground investigation, relying almost entirely on statements from Chinese government sources or highly visible protests to drive its news coverage, which was dominated by inaccurate and negative portrayals of Falun Gong teachings. One such example was Craig Smith’s “Rooting out Falun Gong; China Makes War on Mysticism” (April 30, 2000). While the headline suggests a news piece offering insight into the Chinese regime’s repressive campaign, in reality, the article is little more than Smith’s personal rant against Falun Gong, riddled with his own seemingly secular readings and misinterpretations of Falun Gong writings and beliefs.

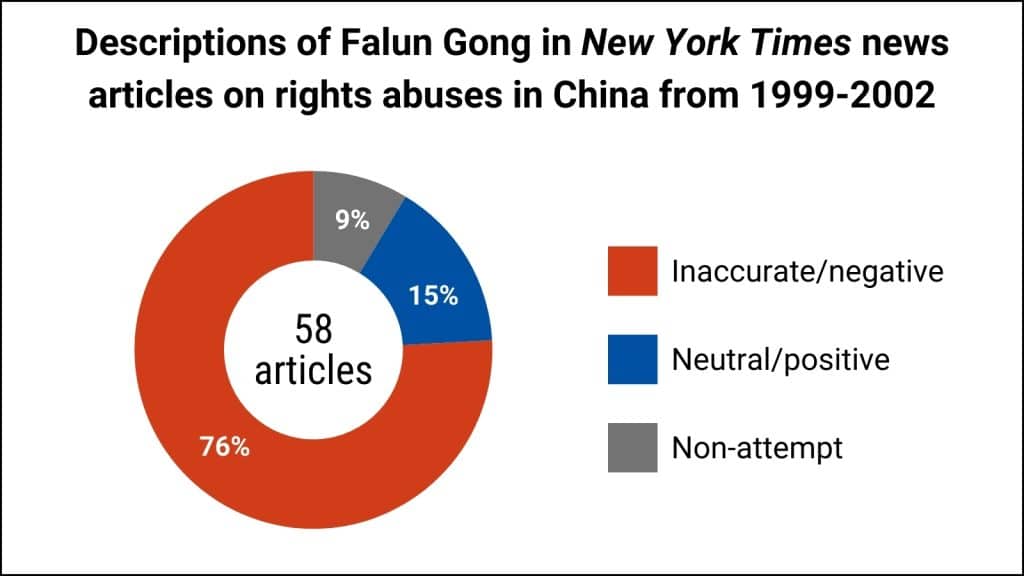

Such portrayals were not an isolated incident, however. From 1999 through 2002, the Times published a total of 58 news articles focused on Falun Gong in China. Among these, 44 carry negative or inaccurate depictions of Falun Gong, with 9 providing a neutral or positive description, and the remaining 5 offering no meaningful characterization.

In terms of substance, only 2 of the 58 articles lead with original, on-the-ground investigation and reporting (as opposed to news triggered by statements or actions of others). One of them was Craig Smith’s “A Movement in Hiding” (July 5, 2001) that is centered around an interview with a single Falun Gong practitioner, “Lloyd Zhao,” but is riddled with false and misleading characterizations of Falun Gong beliefs. The other, Elisabeth Rosenthal’s “Beijing in Battle With Sect: ‘A Giant Fighting a Ghost’” (January 26, 2001) is the most informative work by the Times during this three-year period. However, it features the inaccurate and denigrating “sect” label in the headline and states, as fact, that five Falun Gong believers set themselves on fire on Tiananmen Square, a narrative that the Washington Post would disprove just ten days later with its own original investigative reporting.[10]

Indeed, the Times’ coverage of the self-immolation incident from the outset accepted at face value the Chinese state media’s version of events—that these were Falun Gong fanatics who were harming themselves—and repeated that to its readers, alongside gruesome depictions of the regime’s propaganda emerging from the event.[11] This occurred despite the fact that Falun Gong prohibits suicide and that the so-called believers were performing the meditation exercises incorrectly, among other inconsistencies.[12] The Times’ misleading depictions continued even months after the above-mentioned Post investigation found that a key participant had never been seen practicing Falun Gong.[13]

Private meeting with Jiang Zemin, architect of the persecution

Perhaps the most striking and unique event during this time period, however, was not anything the Times published, but rather, an August 2001 meeting between a Times delegation (including its then-publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr.), and Jiang Zemin[14]—the man identified by the Washington Post less than a year earlier as the principal architect of the crackdown.[15] According to a report by Smith in 2017, the goal of the meeting was to explore the possibility of a Chinese-language version of the Times and perhaps other business interests. The delegation also raised concerns about the New York Times website being blocked in China. Days after the meeting, nytimes.com was unblocked, and remained accessible to Mainland readers for the next ten years. The Times also published excerpts from its exclusive interview with Jiang.[16]

New York Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger meeting with former Communist Party leader Jiang Zemin, 2001

Thus, as the Wall Street Journal and Washington Post were producing Pulitzer Prize-winning and ground-breaking journalism, the crowning achievement of the New York Times during the same period was advancing the Times’ business interests in China, while offering reporting on Falun Gong riddled with inaccurate and negative characterizations.

This ominous beginning set the stage for the next 20+ years of problematic journalism, as the Times ventured further down the path of vilifying Falun Gong beliefs and teachings, while ignoring gross and well-documented human rights abuses against adherents of the spiritual practice.

3. Maligning and Misrepresenting Falun Gong

The New York Times’ characterization of Falun Gong teachings and beliefs has been consistently inaccurate and negative, often following CCP framing of the Falun Gong story.

Soon after the CCP banned Falun Gong and launched its campaign against the group, the CCP was facing international criticism and domestic skepticism over its abrupt and brutal attack on tens of millions of ordinary Chinese meditating in parks. Thus, accompanying the security operation has been a massive propaganda campaign aiming to justify such actions and turn public opinion against Falun Gong. This campaign has included claims—and even fabrications—that Falun Gong is somehow dangerous and an “evil cult.”

The reality was—and is—that Falun Gong is a peaceful meditation and spiritual practice that teaches self-improvement and enhances well-being. Numerous scholars and other experts on Chinese religions have repeatedly affirmed that Falun Gong does not bear the characteristics of a cult and moreover, that the application of such a demonizing label by the regime has been a “red herring from the very beginning.”[17]

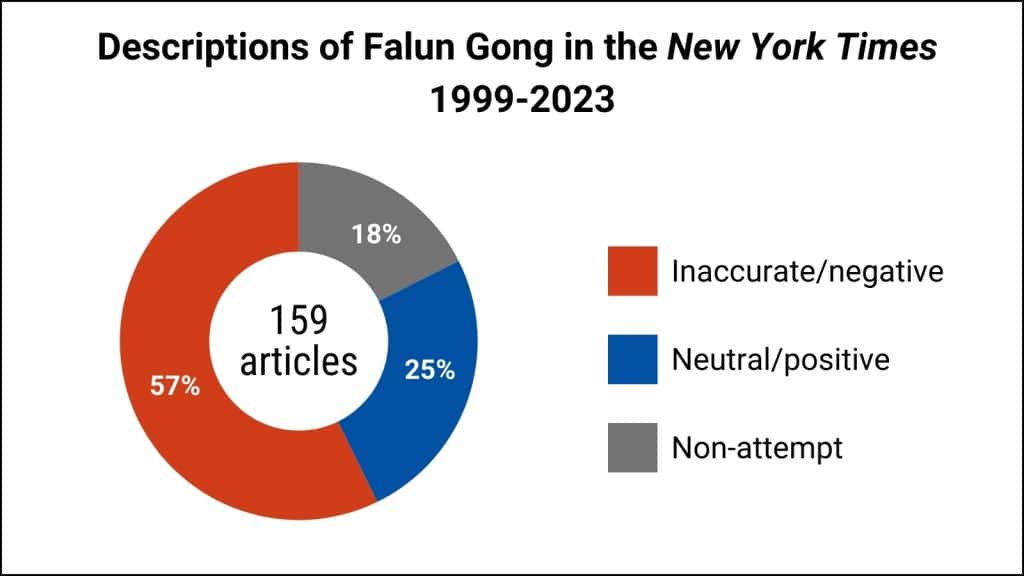

But to look at the Times’ coverage and word choice when it comes to Falun Gong, one would not know this was the case. In fact, the reader is often led to believe the opposite. A review of the dataset of 159 articles published by the Times since 1999 that focused on Falun Gong reveals both frequent inaccuracies and significantly higher frequency in the appearance of CCP-preferred demonizing labels for Falun Gong rather than expert assessments or the lived experiences of practitioners.

Inaccurate, negative terms dominate the narrative

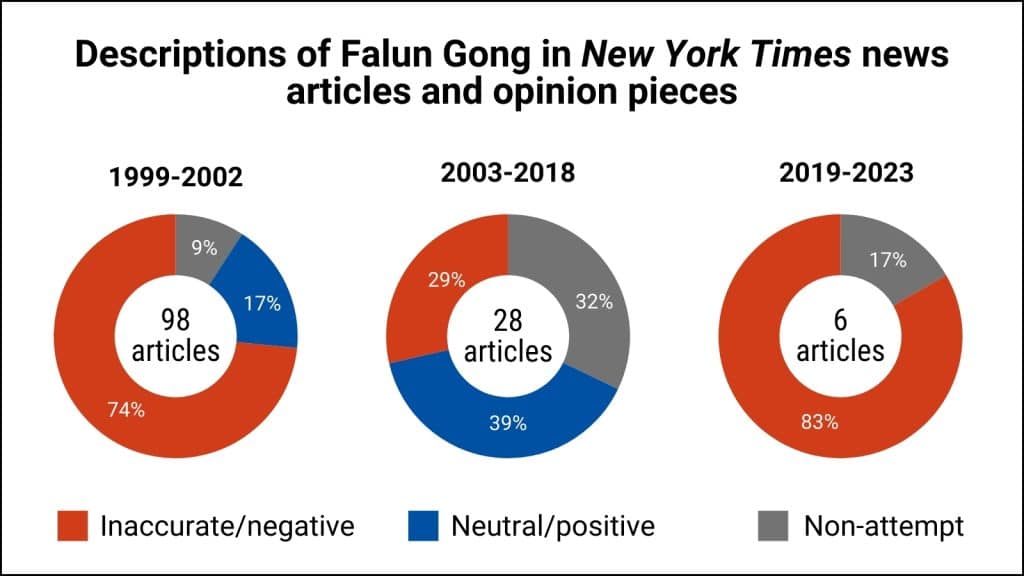

A collective analysis of the descriptions used in all 159 New York Times articles from 1999 to 2023 that focused on Falun Gong found that inaccurate or negative terms were used in 91 articles, while neutral or positive descriptions were used in 40. Minimal descriptions, such as simply referring to the “Falun Gong spiritual movement” without further explanation appeared in 28.[18]

Prioritizing CCP terminology over core Falun Gong tenets

In learning about a new religious movement unfamiliar to most news consumers, Times readers have likely been relying on the paper’s explanations of Falun Gong to understand who this group is and why the CCP has cracked down so violently. One might expect, then, that key aspects of the practice familiar to believers and cited by experts would be a primary source of descriptions.

Yet, the core tenets of Falun Gong’s teachings—Zhen-Shan-Ren (with varying translations)—are almost entirely absent. The phrase, which can be translated as “Truth, Compassion, Tolerance,” is the most basic summation of Falun Gong’s values. At any given Falun Gong event these three words can be found emblazoned on banners or signs; these are prominent in the group’s informational literature; and they appear literally thousands of times in the memoirs, writings, and accounts of adherents. The phrase appears at least 30 times in Falun Gong’s central book, Zhuan Falun. No concept or phrase is more essential to Falun Gong identity or practice; it is the common guiding belief, or tenet, for all adherents. It is thus surprising that Zhen-Shan-Ren appears in only five articles out of the 159 New York Times articles examined. In each instance it is offered as part of a quotation from a Falun Gong adherent; not once is this value or teaching ascribed to the practice by the reporter him or herself.

By contrast, terminology and adjectives originating from China’s Communist Party-state apparatus dominate references to Falun Gong and appear in 72 articles. The terms comprising these 72 instances include: “evil” (61 articles), “dangerous” (15 articles), “secretive” (11 articles), and “deceitful” (1 article). The most common derogatory phrase—central to the Party-state’s anti-Falun Gong propaganda—is “evil cult” (or “evil sect,” as alternatively translated), itself a manipulated translation of the Chinese term xiejiao. This term appeared in 40 articles. In many cases, terms like “evil cult” or “dangerous” were presented as something the Chinese government claimed about Falun Gong, though often without any further information for readers as to why such attribution might be untrue. Elsewhere, words like “obscure” and “secretive” were used by the Times’ own writers, including in headlines or subheadings.

Terms such as “evil cult” and “dangerous” are not value-neutral. Rather, they are loaded, acerbic, damning terms that were deliberately selected by the CCP’s propaganda apparatus in order to forward a repressive political agenda. They are meant to alienate and dehumanize. According to Amnesty International, “the official campaign of public vilification of Falun Gong in the official Chinese press has created a climate of hatred against Falun Gong practitioners, which may be encouraging acts of violence against them.”[19] In this context, the Times, unwittingly or not, has in practice furthered the Chinese state’s repression by spreading and prioritizing such pejorative terms to audiences around the world.

It is worth noting that the relatively objective terms “spiritual movement” or “spiritual group” do appear in 101 articles, but at least 55 of those also include inaccurate or derogatory labels like “sect” (see below)—including in 48 headlines, a more prominent location than the body of the article—arguably offsetting the neutrality of a reader’s perception of Falun Gong.

Frequent use of the inaccurate term “sect”

One of the most common inaccuracies evident in the Times’ reporting is the use of the term “sect” to describe Falun Gong. The term “sect” appears in over one-third of all Times articles on Falun Gong (61 out of 159), but its application to Falun Gong is problematic in several regards. The entry for “sect” in the Oxford English Dictionary[20] is as follows:

- A branch or subdivision of a larger religious group, typically distinguished by differences in doctrine and observance

- depreciative. A religious denomination or group characterized as heretical or departing from orthodox tradition in doctrine and observance, or as dissenting, separatist, or schismatic

- a group pursuing a particular political ideology, typically when regarded as extreme or dangerous.

None of these three definitions applies to Falun Gong. Notably, Falun Gong is not an offshoot that separated from a larger, established religion, nor when using the term “sect” does the Times attempt to list such a group. If anything, the paper’s frequent suggestion that the practice “combines elements of Buddhism and Taoism” would imply it is neither A nor B, but rather, a new creation.

The more significant problem is the often derogatory and negative connotation of “sect.” As the Oxford entry states, it is a pejorative term, and often refers to a group regarded as “extreme or dangerous.” Yet Falun Gong has—even in the face of extreme brutality from the CCP—consistently exhibited a strong commitment to nonviolence. The paper’s repetitive use of the term itself therefore demonstrates an internalization of the CCP’s framing of Falun Gong as nefarious in some way.

This sentiment is then relayed to readers, beginning with an article’s headline. Indeed, so prominent is the Times’ use of the word of “sect” that it appears in a total of 48 headlines, even when not used in the body of the article. This would indicate that it was likely incorporated formally or informally into copy-editor guidelines, a further institutionalization of negative bias against Falun Gong.

The use of sect contrasts with the findings of scholars such as David Ownby, author of Falun Gong and the Future of China, who writes:

My research led to the following conclusions: Falun Gong should be understood as a form of qigong—this is a general name, which might be translated as “discipline of the vital force”—which describes a set of physical and mental disciplines based loosely on traditional Chinese medical and spiritual practices, and often organized around a charismatic master who teaches his followers specific techniques as well as general moral precepts, with the goal of realizing a physical and moral transformation of the follower.[21] [emphasis added]

While the Times has variously employed the term qigong to describe or classify Falun Gong, it has done so sporadically at best, and in many cases used it alongside the term “sect.” The term qigong does not appear in any headlines.

The InfoCenter raised concerns early on over the use of the term “sect” and its inappropriate application to Falun Gong on numerous occasions with the New York Times, but did not receive a response or witness any demonstrable change. To date the paper has described Falun Gong as a “sect” no less than 61 times, and continues to employ the term in spite of its pejorative sense and basic inaccuracy.[22]

Additional inaccuracies

Though not as prevalent as the use of the term “sect,” several other inaccuracies related to Falun Gong appear repeatedly in the Times’ coverage.

One involves the many Times articles that refer to Falun Gong as consisting of “breathing exercises” or “deep-breathing,” a method common to many qigong practices but not part of Falun Gong’s slow-moving exercises. Similarly, the Times repeatedly depicts Falun Gong as harnessing qi through its exercises, another common qigong approach absent in Falun Gong. Such basic inaccuracies appear in at least 12 articles. While seemingly benign, these errors nevertheless betray an ignorant and flawed understanding of Falun Gong, as well as limited engagement with actual practitioners who could have easily clarified these points, which thereby raises questions about the reliability and accuracy of the paper’s broader reporting on Falun Gong.

Other erroneous depictions of Falun Gong are more damaging, such as references to the practice as “secretive”—again implying cultlike behavior. This adjective first appeared in an article in July 1999 and then was not mentioned in Times coverage for many years.[23] However, it reappeared in multiple articles published in 2020, where Falun Gong is described as “secretive” four times, without any explanation as to how the authors arrived at that conclusion. In particular, a Times October 24, 2020 article describes Falun Gong first as “secretive and relatively obscure,” and then later in the same article as “extraordinarily secretive.” Yet this description runs contrary to the fact that Falun Gong practice sites are free of charge (run by volunteers) and open to all worldwide with contact information available online; all Falun Gong teachings are freely available at its website (www.falundafa.org); and there are tens of thousands of personal accounts of experience with the practice published online from people across six continents—hardly the makeup of a “secretive” spiritual practice.

Misrepresentation and sensationalism

Other descriptions of Falun Gong relayed by the Times involve more subtle distortions, such as misrepresentation of the practice’s teachings to falsely imply features such as racism or elevation of relatively minor points, even ones common among many non-Falun Gong Chinese, in order to portray the practice as exotic and strange.

For example, the Times staff seem preoccupied by a belief in the existence of extraterrestrial life, asserting in at least five articles that “aliens” or “extraterrestrials” are part of Falun Gong’s belief system. In fact, in the context of Falun Gong beliefs and daily practice, this is a marginal topic rarely if ever discussed among adherents; it seldom appears in any writings or accounts of practitioners and is mentioned only twice in Zhuan Falun, the core spiritual text of the practice, both times merely in passing. This is quite the opposite of Zhen-Shan-Ren, the core tenets of the practice mentioned above, yet aliens are given the same number of references by the Times as these.

Similarly problematic is the tendency of Times reporters, most notably Craig Smith who wrote for the paper in the early years of the persecution, to cherry-pick quotes or points from Falun Gong writings meant to cast the group as outlandish or deviant. Smith wrote in October 2000 for example that, “Drawing from Buddhist and Taoist traditions, that [Falun Gong’s] cosmology describes multiple dimensions and alien beings, apocalyptic events and segregated paradises for the world’s various races.”[24] The latter point seems to imply that Falun Gong advocates for racial segregation in human society and opposes practices like interracial marriage.

Yet, such an interpretation is wholly inaccurate. Falun Gong practitioners, both in China and elsewhere, are a racially diverse group, while marriages across ethnicities and families with interracial children are extremely common. It is noteworthy that several Falun Gong practitioners have described communicating this to Smith directly. That, however, did not encourage him or others to check their limited reading of a Falun Gong text against the community’s own interpretation and lived practice of it.

As with the claim of secrecy mentioned above, this point from earlier Times reporting has reappeared in the paper more recently. For example, a 2020 article by Kevin Roose cites the inaccurate claim that Falun Gong “forbids interracial marriage,” a false narrative about Falun Gong that the CCP propagates only in the West where racism is a hot button issue. This assertion is notably absent from the CCP’s domestic propaganda inside China.

Internalizing CCP terminology and perspectives on Falun Gong

These mischaracterizations of Falun Gong and its beliefs do not appear to be accidental, given their frequency and continuation even in the face of concerns raised by practitioners or entities like the InfoCenter. Rather, the references—and limited knowledge available about the internal workings of the paper—indicate that the Times, from very early on, had internalized the CCP’s terminology and characterization of Falun Gong.

As early as October 1999, the Times ran the headline “China Enacts Tough Law To Undercut Banned Cult,” immediately relaying to readers at face value the demonizing label the regime was retroactively trying to apply to justify the crackdown on Falun Gong. Months later in April 2000, the Times’ Craig Smith wrote that, “aspects of the movement, or cult, suggest that…,” thereby adopting in his own writing the regime’s designation for Falun Gong.

Such adoption of the term ignores the findings of scholars, like David Ownby, who wrote: “The entire issue of the supposed cultic nature of Falun Gong was a red herring from the beginning, cleverly exploited by the Chinese state to blunt the appeal of Falun Gong and the effectiveness of the group’s activities outside China.”[25] It also contradicts evaluations by peers at other publications like the Wall Street Journal, such as Ian Johnson:

The group [Falun Gong] didn’t meet many common definitions of a cult: its members marry outside the group, have outside friends, hold normal jobs, do not live isolated from society, do not believe that the world’s end is imminent and do not give significant amounts of money to the organization. Most importantly, suicide is not accepted, nor is physical violence…. [Falun Gong] is at heart an apolitical, inward-oriented discipline, one aimed at cleansing oneself spiritually and improving one’s health.[26]

The Times’ prejudice toward Falun Gong seems to have permeated the halls of the paper. Many years later, while preparing for a press conference in New York City, the InfoCenter’s executive director Levi Browde recalls viewing an email thread from a Times reporter who dismissed the event, adding “everyone here knows they’re [Falun Gong] a cult.” “This was around 2008 or 2009,” recalls Browde, who says a PR professional had shown him the email thread on her laptop, which had many Times staff included.

In 2019, such negativity toward Falun Gong was again brought to the fore by former New York Times reporter Ms. Didi Kirsten Tatlow. In written testimony submitted to the China Tribunal in London, Ms. Tatlow says her Times editors presented the “usual arguments” about Falun Gong, claiming practitioners to be “irrational” and “unreliable,” using this to explain their decision to bar her from pursuing further investigation into organ transplant abuses and victimization of Falun Gong prisoners of conscience.[27]

Ramifications

Whatever the reasons for the phenomenon, the Times’ inaccurate portrayals, mischaracterization, and sensationalizing of Falun Gong’s beliefs have significant implications. The evolving portrait of a Falun Gong believer is irredeemably foreign, often disturbing, and a far stretch from the lived reality of actual practitioners or the findings of scholars who have interacted with the community.

The Falun Gong believer that emerges from the Times’ renderings is someone above all else different from you or me. Someone less fully human, perhaps, given their bricolage of bizarre beliefs, and even deserving of the mistreatment being meted out by the Chinese government. In short, an “unworthy victim.”

4. Downplaying the Scale and Severity of Persecution

Often following CCP framing, the New York Times’ quantification and characterization of the persecution in China included factual errors and significant distortions.

The Times’ reporting on the size of the Falun Gong community as well as the nature, and even existence of, the persecution in China often followed CCP narratives or talking points. In some cases, CCP factual errors were repeated verbatim and without attribution, demonstrating an internalization of anti-Falun Gong sentiment at the Times.

Uncritically downsizing the number of Falun Gong practitioners

In several news reports from December 1998 to May 1999, Western media outlets—including the New York Times—published estimates of 70 to 100 million people practicing Falun Gong in China, citing official government sources.

A Falun Gong practice site in Guangzhou, 1998

For example, one of the first such mentions of this figure appeared in a news program aired by China’s own state television in which the anchor tells the audience “over 100 million people are practicing Falun Gong.”[28] Soon after, on February 14, 1999, an official from China’s National Sports Commission, speaking with U.S. News & World Report, suggested that as many as 100 million may have taken up the practice.[29] The official highlighted the costs the practice was saving China’s national health care system, declaring that, “Premier Zhu Rongji is very happy about that.” Later that year, after the April 25 public appeal in Beijing that caught international attention, on April 26, 1999 the Associated Press published an article stating that “with more members than the Communist Party – at least 70 million, according to the State Sports Administration – Falun is also a formidable social network…”[30]

The following day, the Times published a story, “In Beijing: A Roar of Silent Protestors,” by Seth Faison, which stated: “…the Government’s estimate of 70 million adherents represents a large group in a nation of 1.2 billion.”[31] That same day it also published another piece by Joseph Kahn, titled “Notoriety Now for Movement’s Leader,” which asserted:

… Mr. Li has become a guru of a movement that even by Chinese Government estimates has more members that the Communist Party. Beijing puts the tally of his followers at 70 million. Practitioners say they do not dispute those numbers, but they say they have no way of knowing for sure, in part because they have no central membership lists.[32]

But once the CCP announced the ban on Falun Gong in July 1999, the Chinese regime dramatically downsized its estimate to 2 million. This was undoubtedly part of a propaganda campaign to cast Falun Gong as a small and inconsequential group, while downplaying the scale of violations facing believers.

Immediately and without explanation, the New York Times followed suit, reducing its official estimate accordingly. Thus, an October 1999 article states that “the Government puts the number at two million.” Subsequent Times reports repeated this CCP talking point, again, without ever acknowledging the change nor explaining why it differed from the Times’ own earlier reporting.

At the same time, the Times rebranded the accurate 70 million number as nothing more than an unsubstantiated claim by Falun Gong. In October 1999, Erik Eckholm wrote: “…tens of millions claimed by supporters, numbers that cannot be verified.” Furthermore, the Times’ Craig Smith wrote on Jan. 5, 2001: “The number of those followers is impossible to estimate. Chinese authorities say it is under two million—far fewer than the 20 million estimated by one government agency to be practicing the discipline at the height of its popularity in the late 1990’s. Mr. Li, meanwhile, continues to claim 100 million adherents worldwide, most of them in China.” Incredibly, Smith’s description includes a stark factual error—the Chinese government’s estimate in the late 1990s (as outlined above) was not 20 million people practicing Falun Gong, but rather 70 to 100 million, a figure he solely attributes to Mr. Li, which, again, stands in contrast to the Times’ own reporting from 1999.

Later that year, on July 5, 2001, Smith further reported, “Mr. Li says there are 70 million practitioners in China and 100 million followers worldwide, though he has never offered evidence to support that. Closer scrutiny suggests the movement in China never numbered more than several million.” Closer scrutiny reveals, rather, that multiple sources—including Chinese government agencies—reported tens of millions of followers. Also, it reveals that Smith did not even check the archives of his own news company, where that information was easily accessible.

This example of uncritically following the CCP’s changing “facts” demonstrates either a significant lapse in basic journalistic practice, a disturbing trust in the Chinese regime, or a convenient desire to follow CCP talking points—or perhaps all of the above.

Propagating the false narrative that Falun Gong was “crushed”

When the Chinese regime unleashed the crackdown on Falun Gong in July 1999, it is believed that Jiang Zemin, then-CCP leader, aimed to eliminate Falun Gong within three months based on a speech given on July 19, 1999, marking the start of the persecution against the group—an audacious goal given there were tens of millions of people practicing it in China at the time.

It is unclear to what extent Chinese officials believed this to be possible. What is clear is that over the subsequent two years, the Times repeatedly delivered a false narrative to the world that Falun Gong was unable to resist the onslaught against it and had been “crushed” in China. The first such article was on July 23, 1999, just three days after Falun Gong was banned. The Times published an article by Craig Smith titled “Falun Gong Manages Skimpy Rally; Is Sect Fading?”[33]

Soon after, in an August 1999 article about forthcoming trials for Falun Gong coordinators in China, the Times predicted:

With today’s announcement, the campaign is evidently in its third and final stage… The final stage of the campaign is now expected to publicize the punishment of the movement’s leaders as an example to anyone considering ways to challenge the authority of the Communist Party. It is likely to be wrapped up in the coming weeks, before Oct. 1, when the party is planning a huge celebration of its 50 years in power.[34]

This assessment was, of course, strikingly wrong. Twenty-five years later, the campaign of persecution continues—including long prison sentences regularly meted out to Falun Gong practitioners.

Still, throughout 2001 and 2002, and without any evidence suggesting a mass exodus from Falun Gong, additional Times reports all but declared Falun Gong “crushed” in China:

- An August 17, 2001 article by Erik Eckholm said that Falun Gong had “been reduced on the mainland to isolated and desperate remnants.”

- Elisabeth Rosenthal’s April 5, 2002, article said the practice was “now based largely in the United States.”

- A July 9, 2002, article by Erik Eckholm said, “Falun Gong has largely been crushed inside China over the last two years.”

- Daniel Wakin said in a December 19, 2002, article that Falun Gong “has been crushed in China.”

Informed sources indicate these statements by the Times are wholly inaccurate, demonstrating a glaring inability, or unwillingness, to grasp the presence and significance of a community of tens of millions of people across China. Moreover, this community, as scholar Andrew Junker wrote in a 2019 book: “might be the most well organized and tenacious grassroots Chinese protest movement ever to challenge the CCP.”[35]

In May 2009, Falun Gong’s main Chinese-language website, Minghui.org, reported that approximately 200,000 underground “materials sites” existed across China.[36] Materials sites are places where people who practice Falun Gong print leaflets, produce DVDs, or other content that exposes the persecution and debunks anti-Falun Gong propaganda. These sites are operated at a grassroots level across China and usually located in a private residence. Each site provides materials to 100-200 Falun Gong practitioners, who then distribute the materials in their locales. These numbers alone indicate that 20-40 million Falun Gong practitioners are actively working to expose the widespread suppression they face in China. These numbers do not include people practicing Falun Gong in China who do not take part in this form of peaceful resistance.

In 2015, two scholars published an article in the China Quarterly academic journal outlining the ineffectiveness of the CCP’s campaign to suppress Falun Gong, based in part on official Chinese government websites and documents, and its subsequent need to therefore continue the suppression.[37] In 2017, Freedom House published one of the most comprehensive third-party reports on Falun Gong as part of a larger study of religious revival, repression, and resistance in China. Among its top finding is that:

Despite a 17-year Chinese Communist Party (CCP) campaign to eradicate the spiritual group, millions of people in China continue to practice Falun Gong, including many individuals who took up the discipline after the repression began. This represents a striking failure of the CCP’s security apparatus.

Using a different methodological approach from Minghui.org, Freedom House estimated there were 7 to 20 million practitioners in China, a range that has subsequently been quoted by the US State Department and other government agencies.

Thus, a full 13-15 years after the Times proclaimed as fact the demise of Falun Gong in China, credible third parties concluded that tens of millions continued to practice throughout China and that in fact, the CCP’s campaign to crush Falun Gong had failed.

A Chinese citizen in Jiamusi, Heilongjiang Province, reads a banner hung by Falun Gong practitioners in 2018 that reads “Kidnapped by Authorities” detailing persecution cases in the area (Credit: Minghui.org)

Labeling rights violations as a mere “conflict”

Most early Times coverage of the CCP’s campaign against Falun Gong in China, as typified by a July 28, 1999 editorial, denounced the ban with words such as “persecution,” “political campaign,” “crackdown,” “violent,” “harsh” and “propaganda.”[38] By contrast, later coverage framed the persecution as a more even-handed “battle” or public relations “war”—as if there was a level playing field between the largest communist regime in the world and a group of peaceful meditators, or worse, as if what was at stake was merely public image and not widespread imprisonment, torture, and killing of innocents.[39] Falun Gong concerns of ongoing rights abuses were increasingly cast as part of a “PR campaign” by the group, with the merit of the claims neither considered nor investigated with any depth.[40]

This trend has continued throughout the Times’ coverage of Falun Gong, and in fact, been more pronounced in recent reporting. On October 24, 2020, the Times characterized Falun Gong practitioners’ attempts to expose the persecution they face and the human rights abuses committed by the CCP more broadly as a “scorched-earth fight against China’s ruling Communist Party.”[41]

To be clear, the Times is referring to the peaceful and persistent attempts by Falun Gong to sound the alarm about gross human rights abuses they have suffered, while also disclosing the atrocities that dominate the CCP’s rule in China—all of which have involved no violence or even calls for violence—as a “scorched-earth” endeavor? By contrast, 20 years of gross human rights violations, including the detention or imprisonment of millions, rampant torture, and the murder of innocents for vital organs are described elsewhere in the article merely as “strident accounts of persecution” and “accus[ations].” Not a single adjective is used to capture the ferocity of the CCP’s human rights abuses, and certainly nothing approaching the aggressive and scary implications of “scorched-earth.”

Refusing to sign documents renouncing Falun Gong while in Chinese labor camp, the guards there burnt Mr. Tan Yongjie with a hot iron thirteen times. They then left him for dead due to his severe injuries. Mr. Tan managed to escape China and make it to the United States. This photo is from a Houston hospital, 2001.

Fact-check: Key Inaccuracies about Falun Gong Appearing in New York Times Coverage

New York Times coverage of Falun Gong is riddled with inaccuracies, from descriptions of the practice’s exercises and beliefs to the state of affairs within China. The following are some of the most frequent and egregious examples, and explanations of their distortions.

New York Times

Fact-check

False “cult” label:

The most common derogatory phrase—central to the Party-state’s anti-Falun Gong propaganda—is “evil cult” (xiejiao in Chinese). This term appeared in 40 Times articles.

Fact-check: Numerous scholars and experts on Chinese religions have affirmed that Falun Gong does not bear the characteristics of a cult. Moreover, that the application of such a demonizing label by the regime has been a “red herring from the very beginning.”[42] According to the Washington Post, “It was [former CCP leader] Jiang who ordered that Falun Gong be labeled a ‘cult,’ and then demanded that a law be passed banning cults.”

False “sect” label:

The New York Times has inaccurately labeled Falun Gong a “sect” over 60 times. This term was used in 48 headlines, such as “Beijing Protest By Falun Sect Brings Arrest Of Hundreds.”

Fact-check: The term “sect” is a pejorative term that often refers to a group regarded as “extreme or dangerous.” It also implies that a faith is part of or an offshoot of an existing religion. Falun Gong has remained entirely peaceful despite widespread violence used against it in China. It is also an independent spiritual practice separate from other religions, though its teachings refer to principles from Buddhism and Daoism.

False “racist” label:

Several articles falsely claim or imply that Falun Gong “forbids interracial marriage.”

Fact-check: Falun Gong does not forbid interracial marriage. In fact, interracial marriages and multi-racial families are extremely common in the Falun Gong community, including among the Falun Dafa Information Center’s own staff and leadership.

Erroneous depictions of exercises:

Multiple articles describe Falun Gong exercises as “deep breathing” practices.

Fact-check: Though a relatively benign inaccuracy, practicing Falun Gong does not involve “deep breathing”—a mistake that indicates the author has little-to-no understanding of Falun Gong itself.

Faulty figures:

New York Times articles inaccurately represent the number of Falun Gong practitioners in China as being 2 million or claim Chinese government estimates had been 20 million in the late 1990s.

Fact-check: Multiple Chinese government sources in the late 1990s asserted that 70 to 100 million people were practicing Falun Gong. Initially, the Times appropriately cited these figures, but subsequent reports adopted the government’s sharply reduced figure of 2 million without acknowledging the change from the Times own prior reporting. Furthermore, the Times then erroneously attributed the 70 million estimate solely to Falun Gong.

Falun Gong “crushed” in China:

The Times repeatedly portrayed Falun Gong as having been “crushed” by the CCP, later stating that it was “based largely in the United States.”

Fact-check: Nearly 25 years after the CCP banned Falun Gong, the practice survives in China, where the largest proportion of believers live. In a 2017 report from Freedom House, researchers estimated that 7-20 million continued to practice in the country, representing a “striking failure” of the regime’s campaign to wipe out the practice. Only an estimated 10,000 reside in the United States.

Fact-checks on

New York Times’

Inaccuracies

False “cult” label:

The most common derogatory phrase—central to the Party-state’s anti-Falun Gong propaganda—is “evil cult” (xiejiao in Chinese). This term appeared in 40 Times articles.

Fact-check: Numerous scholars and other experts on Chinese religions have repeatedly affirmed that Falun Gong does not bear the characteristics of a cult. Moreover, that the application of such a demonizing label by the regime has been a “red herring from the very beginning.”[42]

False ‘sect’ label:

The New York Times has inaccurately labeled Falun Gong a “sect” over 60 times. This term was used in 48 headlines, such as “Beijing Protest By Falun Sect Brings Arrest Of Hundreds.”

Fact-check: The term “sect” implies that a faith is part of or an offshoot of an existing religion. Falun Gong is an independent spiritual practice, though its teachings refer to principles from Buddhism and Daoism.

False ‘racist’ label:

Several articles falsely claim or imply that Falun Gong “forbids interracial marriage.”

Fact-check: Falun Gong does not forbid interracial marriage. In fact, interracial marriages and multi-racial families are extremely common in the Falun Gong community.

Erroneous depictions of exercises:

Multiple articles describe Falun Gong exercises as “deep breathing” practices.

Fact-check: Though a relatively benign inaccuracy, practicing Falun Gong does not involve “deep breathing.”

Faulty figures:

New York Times articles inaccurately represent the number of Falun Gong practitioners in China as being 2 million or claim Chinese government estimates had been 20 million in the late 1990s.

Fact-check: Multiple Chinese government sources in the late 1990s asserted that 70 to 100 million people were practicing Falun Gong. Initially, the Times appropriately cited these figures, but subsequent reports adopted the government’s sharply reduced figure of 2 million, while erroneously attributing the 70 million estimate solely to Falun Gong.

“Crushed”:

The Times repeatedly portrayed Falun Gong as having been “crushed” by the CCP, later stating that it was “based largely in the United States.”

Fact-check: 24 years after the CCP banned Falun Gong, the practice survives in China, where the largest proportion of believers live. In a 2017 report from Freedom House, researchers estimated that 7-20 million continued to practice in the country, representing a “striking failure” of the regime’s security apparatus. Only an estimated 10,000 reside in the United States.

5. Deafening Silence

The New York Times has been exceptionally silent on atrocities against Falun Gong practitioners, including the forced organ harvesting of prisoners of conscience. Other religious, ethnic, or regional minorities in China have not been ignored by the New York Times like Falun Gong.

Chinese police arrest a woman for protesting in Tiananmen square for the right to practice Falun Gong, 2000. (Chien-min Chung, Associated Press)

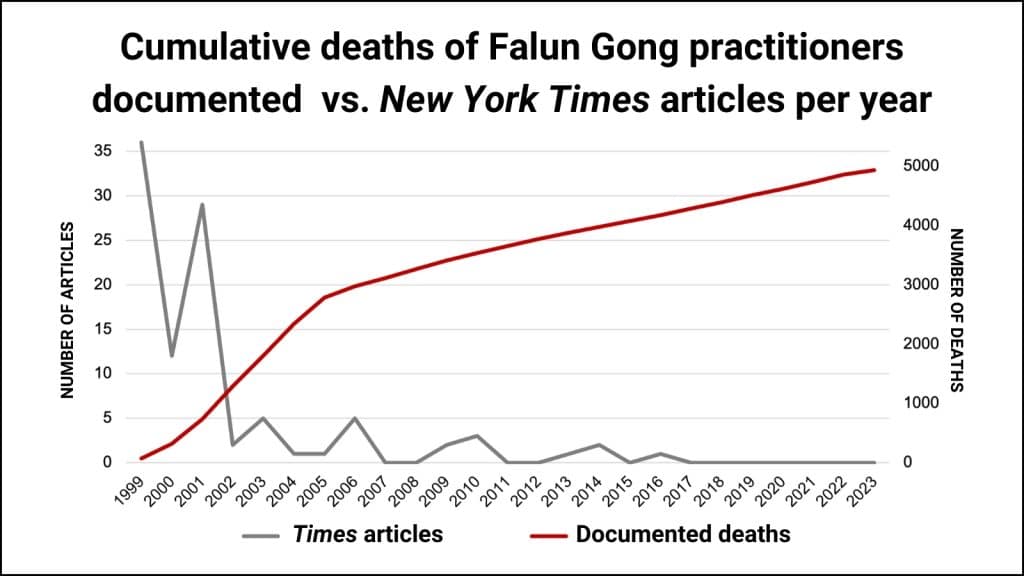

In addition to the New York Times’ reporting echoing the regime’s claims to have succeeded in crushing Falun Gong, the pattern of subsequent reporting demonstrates the paper’s internalization of this assumption, thereby not only ignoring Falun Gong’s survival but also the widespread and brutal human rights violations suffered by those who practice. Indeed, a close review of the Times’ coverage from 1999 to the present day demonstrates a dramatic drop in reporting beginning in late 2001, even as torture and deaths of practitioners from police abuse increased. Over the past decade, the paper has been almost entirely silent on the persecution of Falun Gong in China, even as its reporters have demonstrated prowess and attention to similar repressive campaigns meted out by the CCP against other ethnic and religious minorities, notably Uyghurs and Tibetans.

Declining coverage amid rising reported deaths

Early reports on the Chinese government’s crackdown on Falun Gong were fairly numerous (though reporting during this time shows a lack of understanding of the Falun Gong community, beliefs, and practices). However, Times coverage on the Falun Gong human rights crisis in China plummeted in 2002 and has remained sparse even though severe repression has continued. Meanwhile, the documentation of rights abuses, including forced labor, torture, deaths in custody, and later forced organ harvesting has grown, only to be largely ignored by the Times.

Graph depicting the number of Falun Gong deaths documented compared to the number of articles published by the New York Times about rights abuses against Falun Gong practitioners.

Gaps in coverage

One glaring gap in the Times’ coverage is the absence of articles on reports about Falun Gong by major human rights groups across various periods of time. While some early stories are sourced from a small NGO in Hong Kong reporting on protests and arrests of practitioners, later on, more comprehensive studies by international NGOs triggered no articles. These include a 2002 report by Human Rights Watch which highlighted the false “rule of law veneer” that the regime was using to retroactively justify the ban on Falun Gong.[43] Another was a 2013 report by Amnesty International documenting the abuses faced by practitioners and other detainees in the “re-education through labor camp” system, as well as the continued detention of many in various forms of extralegal facilities even after the presumptive abolition of that network of camps.[44] And more recently, the Freedom House report mentioned above, which included: verification of over 900 cases of Falun Gong practitioners sentenced to prison based on Chinese government verdicts, a budget estimate for expenses related to security forces targeting Falun Gong drawing on Chinese government websites, and interviews with human rights lawyers who had seen firsthand the mistreatment suffered by their Falun Gong clients.[45]

None of these reports were covered by the Times, although other major international media outlets reported upon them.

Burying the forced organ harvesting story

Another major news story ignored by the Times was both early reports and later documentation of organ transplant abuses committed by the regime against Falun Gong and other prisoners of conscience. It was in 2006 that reports and evidence first emerged indicating that not only death-row prisoners but also prisoners of conscience—especially Falun Gong practitioners—were being medically profiled, killed, and used as a source for organ transplants in China.[46] While the accusations were initially met with skepticism, several individuals, including Canadian lawyer David Matas, former Canadian official David Kilgour, and American journalist Ethan Gutmann conducted independent investigations, alongside additional reporting from researchers within the Falun Gong community. In 2006, Matas and Kilgour produced their first report in which they concluded that forced organ removal from people who practice Falun Gong was indeed happening.[47] In 2014, Gutmann published a full-length book, The Slaughter, outlining his findings, which also included cases of Uyghur Muslim prisoners being killed.[48] Yet the New York Times found no need to either cover these findings nor investigate the situation of their own accord. Indeed, it took ten years before an article mentioning this form of abuse was published—in August 2016—but its headline and content included more emphasis on denials by Chinese officials and “anti-cult” groups with ties to the CCP than on an objective consideration of the facts.[49]

Notably, in 2019, the China Tribunal, an independent panel of well-respected experts on international law and China, conducted an extensive review of the evidence of forced organ harvesting, including hearing from over 50 witnesses, including journalists, researchers, doctors, and former Chinese detainees. The panel published its full judgment in March 2020, concluding that, “forced organ harvesting has been committed for years throughout China on a significant scale and that Falun Gong practitioners have been one—and probably the main— source of organ supply.” The rigorous work of the tribunal and its confident conclusion drew widespread media attention, including reports in the Guardian, Reuters, Sky News, the New York Post, U.S. News and World Report, the Sydney Morning Herald, and dozens of other outlets.[50] The New York Times, however, was silent.

In fact, the Times actually had the opportunity to be a leader on the organ harvesting story, as its reporter Didi Kirsten Tatlow was eager to pursue it and had invested time in initial investigations in 2015. Yet, her experience demonstrates that the paper’s silence was not necessarily the result of inattention, but at least in some cases, deliberate editorial decisions. In written testimony that Tatlow provided to the China Tribunal, she noted:

I’d like to say that it was my impression the New York Times, my employer at the time, was not pleased that I was pursuing these stories [on organ transplant abuses], and after initially tolerating my efforts made it impossible for me to continue.

She goes on to relay how editors were dismissive of legitimate concerns that organs had been harvested from prisoners of conscience, even after Ms. Tatlow herself had overheard an exchange between two Chinese doctors indicating that this had occurred, that it appeared to be common knowledge among some medical specialists, and that a reported ban on such practices was not well-known. When she tried to broaden her investigation in this direction, her editors refused, seemingly believing the Chinese government when it stated that “the organ donation issue in China had been solved by the state’s admission that they had used prisoner organs and its promise of Dec. 14 they no longer were doing so.” Tatlow was told there was “nothing new” to the story, while one editor commented that people who believed this was happening were on “the outer fringes of advocacy,” in other words, “not rational.” She further relayed that she suspected this series of articles contributed to a February 2017 decision not to promote her, against the advice of regional editors.

Beyond this particular story, her testimony hints at broader bias against investigating abuses against Falun Gong practitioners, stating that “the usual arguments were presented” and “It was clear to me that the issue was unwelcome.” Such perceptions appear to have taken hold among the paper’s editors despite, as noted above, a plethora of non-Falun Gong sources and documentation pointing to ongoing, widespread, and severe violations occurring across China.

Contrast to coverage of Uyghurs and Tibetans

The above data and analysis reveal an alarming discrepancy between the Times’ reporting and the rights abuses faced by Falun Gong practitioners, including as documented by independent human rights groups and other experts. A similar review of coverage pertaining to Uyghurs and Tibetans reveals an almost parallel but diametrically opposed universe: a plethora of news stories highlighting the plight of persecuted individuals, investigations into the structure of the campaigns, and op-eds giving voice to victims and their relatives. This offers two additional insights—first, that the Times is capable of in-depth, sensitive, and accurate reporting of religious and ethnic persecution in China and, second, that the dearth in coverage of Falun Gong cannot be explained solely based on the constraints the CCP creates for human rights reporting in China more broadly.

News stories appearing in the New York Times during the 15-year-period from Jan 2009 through December 2023 that included focused reporting on each community (i.e. mentioned in the headline or lead paragraph), including regarding human rights abuses, protests or unrest, diplomatic action, or other events.

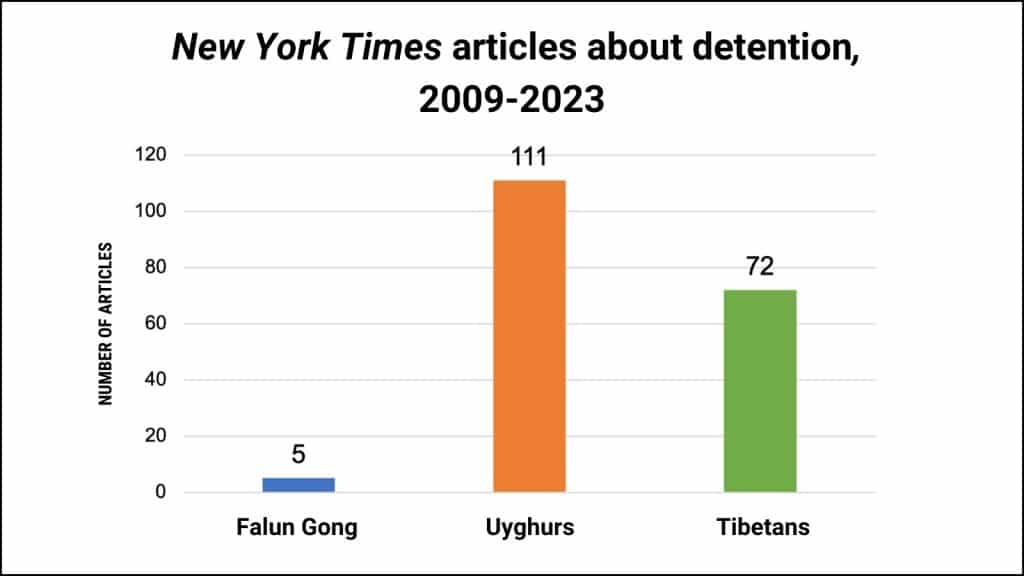

News stories appearing in the New York Times for the 15-year period from 2009 to 2023 that included references to imprisonment, detention, or arrests in the headline or lead paragraph regarding each community.

Besides the sheer differences in scale of reporting, a review of articles published since 2009 regarding both Uyghurs and Tibetans provides a relevant case study for comparison of how the Times approached reporting on these also persecuted and maligned minorities.

Three aspects of the reporting and their difference from the coverage of Falun Gong are especially notable:

Many articles on individual, persecuted members of the minority: The Times has repeatedly, and with good cause, published articles spotlighting the detention, trial, and imprisonment of individual Uyghurs and Tibetans, covering both prominent members of these communities and relatively low-profile individuals. Such coverage is typically very sympathetic to the victim, including interviews and quotes from relatives, supportive policymakers, or human rights advocates. One notable example is that of Ilham Tohti, a Uyghur scholar and website administrator who was detained in January 2014 and sentenced eight months later to life in prison after clearly politicized and sham legal proceedings; Tohti’s daughter lives in the United States. Between 2009 and 2016, the Times published at least 20 articles about his plight, including previous detentions, following his case closely from his latest arrest, through to his trial, sentencing, appeal, international condemnation, and a human rights award he received, as well as an op-ed by his daughter about this case.[51] A similar case was that of Tibetan entrepreneur and language advocate Tashi Wangchuk, who was jailed for five years, partly in reprisal for providing an interview to the Times; his case too was followed closely by the paper with at least 10 articles.[52]

While Tohti and Tashi are particularly prominent individuals and their cases received a uniquely high degree of attention even among reporting on abuses facing Uyghurs and Tibetans, other lower profile individuals also had articles in the Times dedicated to their cases. These included a 2010 article on three Uyghurs sentenced for running a website,[53] a Uyghur journalist jailed for 15 years for sharing information about clashes in Urumqi,[54] and a number of other disappeared Uyghur poets and individuals.[55] With regards to Tibetans, Times reporting included at least four articles about the death in custody of prominent Tibetan Buddhist abbot Tenzin Delek Rinpoche in 2015,[56] multiple articles on individual monks,[57] religious leaders,[58] filmmakers, or musicians[59] being jailed or freed from prison,[60] and over 83 articles on various cases of Tibetans self-immolating in protest against CCP repression. Many articles also favorably profile acts of grassroots dissent like photocopying,[61] Tibetan bloggers,[62] or initiatives to salvage Tibetan culture.[63]

All of these stories were arguably deserving of such coverage and international attention, while entailing risks for Times reporters and sources. From this perspective, the contrast with the paper’s reporting on Falun Gong is stark. Even when the Times has reported on the persecution of Falun Gong, it has typically lacked the humanizing, personal focus evident in the above examples. A few articles in the early years of the persecution reported on public trials of Falun Gong coordinators but they often used Chinese government information as the primary source and there was no follow-up reporting. Two articles by former China correspondent Andrew Jacobs, in 2009 and 2013, highlighted the plight of a small number of Falun Gong detainees and torture survivors in the aftermath of the Beijing Olympics[64] and a note from a labor camp prisoner found in a Kmart product.[65] But these were by and large the exception and no such pieces have been published since. Given the sheer scale of ongoing imprisonment of Falun Gong practitioners across China, the many cases of deaths in custody, the independent documentation of these abuses, and the availability of interviewees outside China, the difference with coverage of Uyghurs and Tibetans is glaring.

Investigations of the regime’s repressive tactics: Even as stories of individual victims help put a human face on faraway suffering, investigations into the architecture of a repressive campaign by the CCP can be even more important for enabling international audiences to understand the full scope of such persecution, and to galvanize action against it. Here too, the Times’ reporting, especially on conditions facing Uyghurs since 2017, displays a degree of expertise, dedication, and resourcefulness absent in reporting on the Falun Gong crisis. Notable examples include reports from 2018 on mass detentions and “transformation” of Uyghurs;[66] one from 2019 on large-scale sentencing of Uyghurs to prison;[67] and investigations from 2020 of forced labor use connected with face masks and battery supply chains.[68] Other investigations into the crisis in Xinjiang—including ones linking abuses to Chinese leaders—relied on sources such as “obscure government websites,”[69] leaked internal documents,[70] and secretly recorded videos.[71] With regards to Tibet, the Times gave strong coverage to investigative reports by groups like Human Rights Watch on topics such as security expenditures,[72] monetary rewards for reporting to police on acts of dissent,[73] and mass relocations.[74]

Many of these same sources have been widely available with regards to the persecution of Falun Gong. Indeed, tactics like “transformation” have been central to the regime’s anti-Falun Gong campaign long before they were deployed against Uyghurs, while the offer of monetary rewards to incentivize reporting by ordinary Chinese on Falun Gong practitioners has been well-documented.[75] In addition to being publicized by entities like the InfoCenter,[76] these tactics and sources have also been found independently and referenced in reports by human rights researchers,[77] scholars,[78] documentary filmmakers,[79] and policy research entities like the U.S. Congressional-Executive Commission on China.[80] Yet, these original—and verifiable—materials, the subsequently published research, and other easily accessible similar sources of information have been entirely ignored by the Times if they touched on Falun Gong.

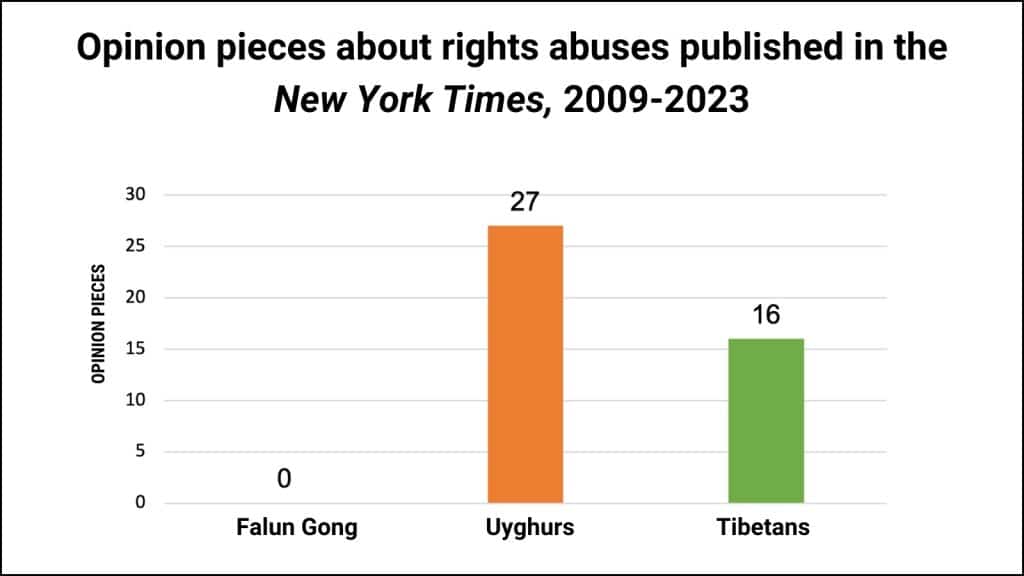

Op-eds, columns, and editorials on rights abuses: Another notable area of contrast is evident in the opinion section of the Times. Since 2009, the Times has published 27 op-eds or editorials about the human rights crisis facing Uyghurs. That included 10 authored by New York Times staff (six editorials and four columns) and 12 by foreign scholars or human rights advocates. They have also given space five times for Uyghurs themselves to share stories of the suffering in their homeland and the fate of detained or missing parents. Similarly, the Times has published 16 op-eds, editorials, or letters to editor on the plight of Tibetans in China. This too included three authored by the paper’s staff, nine by scholars, rights advocates, or supporters (including three by Chinese activists), and four by Tibetans themselves. The large number of articles by the paper’s staff—especially the editorials—demonstrates the publication’s clear position in supporting these communities’ rights and condemning the violent repression they face. The many articles published that were authored by members of these communities offers important amplification for their own voices to reach an international audience.

Yet, during this same period, the Times published exactly zero editorials, op-eds, or letters to the editor about the suffering of Falun Gong practitioners and their families in China. One column was published in 2009 by columnist Nick Kristoff highlighting the technological prowess of overseas Falun Gong practitioners and how their tool for bypassing China’s Great Firewall was aiding anti-government protesters in Iran. This relative dearth was not necessarily for lack of submission attempts, though editorials and columns need not rely on outside contributors.

Even during the first decade of the Falun Gong persecution from 1999-2008, when the crackdown was perhaps fresher in people’s minds, the contrast with more recent space given to Uyghurs and Tibetans, is notable. During that period 14 editorials, op-eds, or letters to the editor about the persecution faced by Falun Gong practitioners in China were published. Of these, the largest contingent were letters to the editor (five) rather than full-length articles. Only two editorials were published that condemned the persecution of Falun Gong believers in China, one in July 1999 shortly after the launch of the persecution[81] and one in 2001 when research showed the regime was sending healthy practitioners to psychiatric hospitals.[82] Four op-eds were published by scholars or Chinese activists who condemned the persecution. Notably, two other op-eds—one by a scholar and one by a former Times correspondent—took a position that appeared to be defending Beijing’s violent crackdown, with the latter referring to Falun Gong as a “cult” and concluding that “no wonder Beijing feels insecure.”[83] Most notably, there were no op-eds or letters published by an ethnic Chinese Falun Gong practitioner. Only one letter to the editor by a British Caucasian practitioner was published in November 1999.[84] There were no op-eds by torture survivors nor by the many relatives of jailed Falun Gong practitioners living abroad. Based on the InfoCenter’s own efforts and interviews with members of the community, this is not because no submission attempts were made.

Articles in the Opinion section—op-eds, editorials, columns—from 2009 to 2023 pertaining to each of the three human rights crises.

Coverage compared to community size and location in China

The greater, more accurate, and more sympathetic coverage of repression facing Tibetans and Uyghurs compared to Falun Gong practitioners is even starker when one considers the relative size of the communities. According to Freedom House’s 2017 report, there were 6-8 million Tibetan Buddhists in the PRC, approximately 10 million Uyghur Muslims, and 7-20 million Falun Gong practitioners. Such estimates indicate that the Falun Gong community in China is at least as large—if not larger—than these two other persecuted minorities. Estimates by the Minghui website place the number of practitioners in China at 20-40 million and, as noted above, before the persecution, the number of practitioners totaled at least 70 million, even according to the Times’ own reporting.

Moreover, Falun Gong is a faith community located across China and, until recently, was well-known to be the largest contingent of prisoners of conscience in the country, one that has received some of the most brutal treatment. For example, a 2009 US State Department report relayed that “Some foreign observers estimated that Falun Gong adherents constituted at least half of the 250,000 officially recorded inmates in RTL [re-education through labor] camps, while Falun Gong sources overseas placed the number even higher.”[85] More recently, scholar Andrew Junker reflects in his 2019 book:

Without a doubt, Falun Gong ranks as one of, and by some measures perhaps the most, severely persecuted groups in the reform era. Moreover, multiple third-party sources have alleged that the CCP consistently singled out Falun Gong for extraordinary degrees of state violence and coercion.

When taking place against Falun Gong and throughout China, violations like surveillance, arbitrary detention, torture, forced labor, and deaths in custody arguably have even greater implications for the rule of law, freedom for the majority of citizens, and potential complicity of foreign businesses than violations isolated to relatively sparsely populated regions such as Tibet and Xinjiang.